“When tillage begins, other arts follow. The farmers, therefore, are the founders of human civilization.”

Daniel Webster

Scientific American: “Old Art Offers Agricultural Info” [*]

Scientific American: “Old Art Offers Agricultural Info” [*]

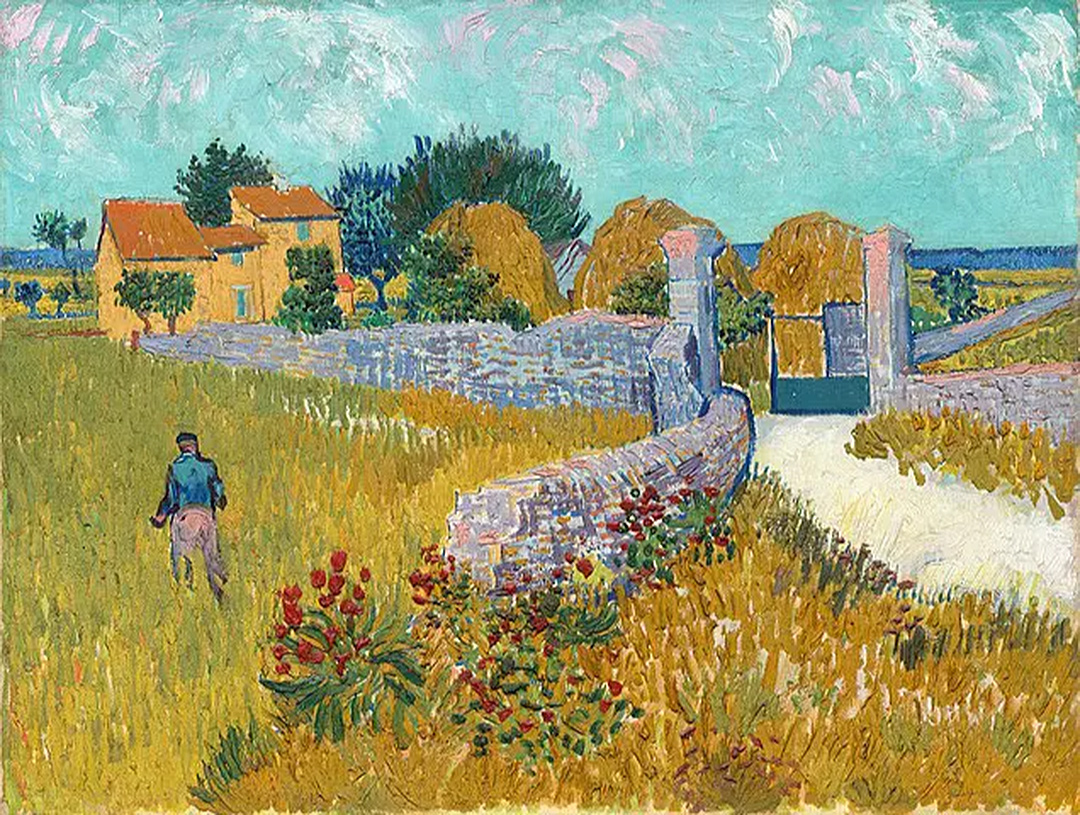

“Art museums are filled with centuries-old paintings with details of plants that today give us clues about evolution and breeding practices. Full Transcript Pieter Bruegel’s iconic 1565 painting The Harvesters hangs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The work depicts peasants cutting stalks of wheat nearly as tall as they are. “Nowadays, if you walk through a wheat field, you basically see that wheat is about knee-height. The short stature is essentially a consequence of breeding from the second half of the 20th century.” University of Ghent biologist Ive De Smet. Selective breeding favored genes for reduced height, because they came along with genes for increasing yields to feed a growing population. De Smet says wheat is just one example of how historical artwork can allow us to track the transformation of food crops over time. He teamed up with art historian David Vergauwen of Amarant to catalogue such artwork around the world.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide: “The American Agriculturist: Art and Agriculture in the United States’ First Illustrated Farming Journal, 1842–78” [*]

Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide: “The American Agriculturist: Art and Agriculture in the United States’ First Illustrated Farming Journal, 1842–78” [*]

“The American Agriculturist (1842–51, 1853–present), a popular trade periodical based in New York City that disseminated practical advice concerning the care, management, and improvement of the farm and rural home, has long been recognized by historians as one of the most significant farming publications of the nineteenth-century United States. Frank Luther Mott, author of the seminal A History of American Magazines (1931), stated that the Agriculturist “reached what is perhaps the most distinguished position ever held by an American agricultural periodical” in the wake of the US Civil War. Similarly, agricultural historian Earl W. Hayter deemed the Agriculturist to be an “authoritative” and “leading” publication that “set the pattern” for rural communities. This sentiment is furthered by contemporary historian R. Douglas Hurt, who lauds the Agriculturist as one of the two most important periodicals in the antebellum United States, and Albert Lowther Demaree—author of the authoritative (and only) monograph on the subject, The American Agricultural Press (1941)—who observed that the Agriculturist had “a more notable history than any of its rivals,” calling it one of the “most popular and influential journals of its day.””

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

National Endowment for the Arts: “From Field to Canvas” [*]

National Endowment for the Arts: “From Field to Canvas” [*]

“Frank Muller has agriculture in his blood. He was raised on a farm, and now runs Muller Ranch in Yolo County, California, northwest of Sacramento, with his two brothers, son, and nephew. The ranch boasts several thousand acres of walnut groves, sunflowers, vineyards, tomato fields, almond trees, and pepper plants. But despite his close ties with the landscape and all it produces, he said the inherent beauty of his farmland once escaped him. “I’ve been to the finest art galleries all over the world,” he noted, “but when you look at these Impressionist paintings of Paris and the countryside, I never thought that our farms in our area could look like that.”

Through his involvement with Art and Ag, a project of NEA grantee YoloArts, his line of sight has shifted. For the past decade, Art and Ag has invited farmers to open their land to local artists, providing unique opportunities to capture private landscapes that would otherwise remain inaccessible and unseen. In turn, money raised through art sales goes toward preserving the farmland of Yolo County, which boasts 255,000 acres of what is considered to be prime farmland.

The interaction has proven to be mutually beneficial. “From a farmer’s standpoint, we’re able to honor what they’re doing, help them tell their story about the value of the land,” said Danielle Whitmore, executive director of YoloArts. Meanwhile, artists gain a new creative outlet and a greater sense of where they live.”*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

AG Daily: “20 Historical Paintings That Say What’s on Every Farmer’s mind [*]

AG Daily: “20 Historical Paintings That Say What’s on Every Farmer’s mind [*]

“Have you ever wanted to get inside of the heads of artists and wondered what their paintings could be saying? We had a little fun here at AGDAILY and put the words and thoughts of farmers to some famous agricultural paintings. Don’t be surprised if you were thinking the same things that these folks were!”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

Blend Radio and TV: “Agriculture as an Art Subject” [*]

Blend Radio and TV: “Agriculture as an Art Subject” [*]

“Agriculture has been an art subject since the Mesolithic period. In some eras since then it seems to have been prominent but, in most eras, rarely seen. We know everyone has to eat, so agriculture ought to be an important subject. But kings and emperors that historically have commissioned art have wanted themselves or events in their lives recorded. Leaders of religion have needed idols to worship or paintings and sculpture to help focus worship.

Paintings, where the primary subject is agricultural life, have been uncommon in most of art history. Historically, we see most art as an agricultural subject during times when people are the most in control of their own lives.

The first artists to record agricultural activity were painters. Their subjects were the first domesticated animals. Cattle and goats were depicted alone or sometimes with herdsmen. Stylized pictographs on rock walls in shallow caves or plastered walls in areas from Turkey to the Sahara were done from 8000 to 3000 B.C. during the transition time from people living nomadic lives as hunter-gatherers to settling in communities to raise crops and livestock. This was a time when agriculture also influenced design. The practice of growing crops in rows, as well as regular patterns in weaving wool and flax for cloth, influenced the repetitive decoration of pottery, plastered walls, and jewelry making.

After the Neolithic period, agriculture was not emphasized in art for many centuries. This was a period of empire-building in the Middle East. Strong kings used artists and sculptors to depict their conquests. Goddess images representing fertility, related to agriculture, were common, but agricultural sculpture or painting was not. Exceptions were Egypt and Crete, two ancient civilizations where cattle and crops were depicted in frescoes. In Egypt, the paintings showed how cattle were used to provide food, power for plowing and grinding grain into flour. The frescoes were painted on the tomb walls of Egyptian royalty. In Crete, the artwork seems to indicate bulls had a religious significance and were pictured as part of a ritual, not in an agricultural sense.”*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.