“Our perfect companions never have fewer than four feet.”

Colette

[Please scroll down for the gallery.]

Looking at the Masters: Painting Farm Animals [*]

Looking at the Masters: Painting Farm Animals [*]

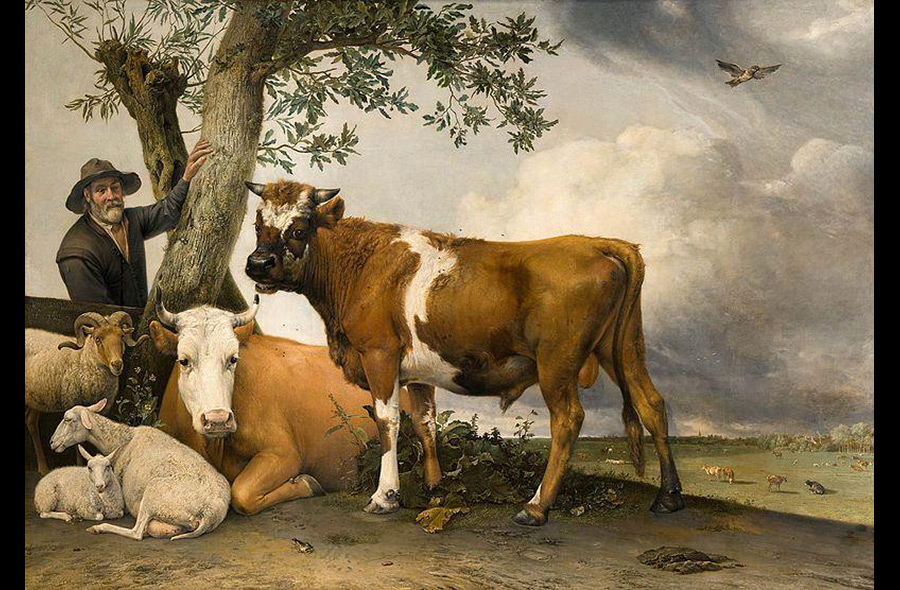

“Dutch painters of the 17th Century were the first European artists to start painting landscapes, because land was owned by commoners as well as by nobles. Throughout the history of art, the subject matter that was most depicted was an indication of what was most important at the time. The newly freed Dutch had no king, and the various new Protestant churches had no single religious authority as previously exercised by the Catholic church. The Dutch became the merchants and tradesmen of Europe, and most trading ships sailed into the port of Amsterdam, where goods were then distributed to the rest of Europe. The Dutch owned their land and their homes, and they looked for small works of art that would fit on the walls of their small homes. The people, rather than the church or state, became patrons of the arts, and a thriving art market developed as a result. Three new subjects were added to painters’ repertoire: genre (paintings of everyday life), still life, and landscapes. European artists frequently painted horses and dogs since they were commissioned by the wealthy owners. Even though the Dutch were responsible for initiating landscape painting, ordinary farm animals were painted by a very few artists, but those artists were masters.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

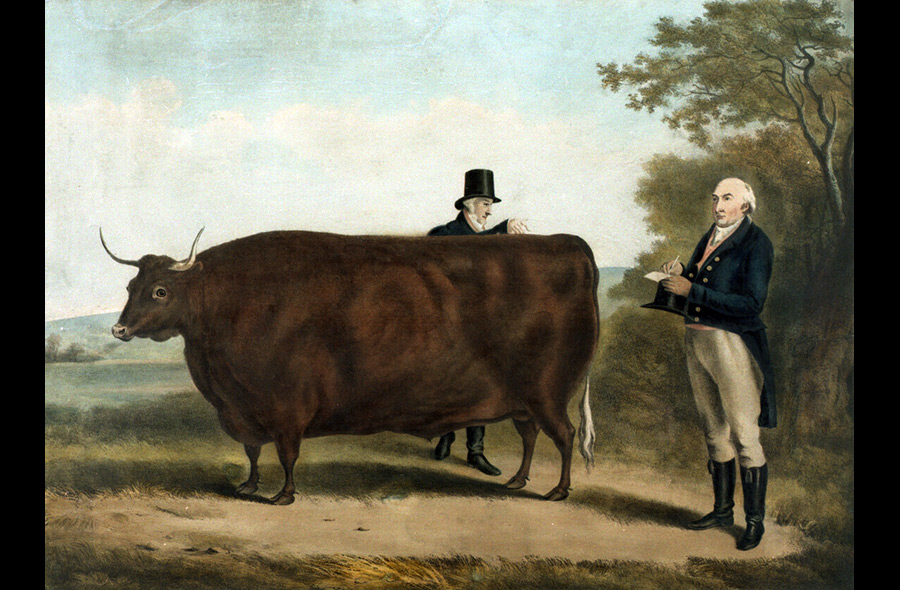

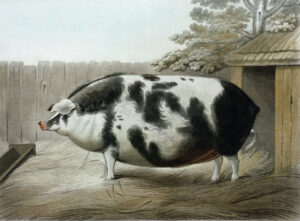

“Livestock portraiture depicting prize animals (cattle, oxen, pigs and sheep) began to appear in the mid-eighteenth century. We derive much historical value from these commissioned paintings through their collective recording of the process of English livestock improvement. It was a period in which livestock was being altered from medieval to modern purposes. In a time of rapid population increase, these adaptations were designed for one end: the production of meat to cater for the ‘the growing demands of the urban tables of Britain’ (Trow-Smith, 1957).

We consumed not only the meat. New developments in the history of printmaking, such as mezzotints, aquatints and lithographs, emerged contemporaneously with the period of agricultural reform. A surge in the interest of scientific approaches to breeding, and the ‘mania for improvement’ (Walton, 1984), meant enthused audiences readily consumed the reproductions as fashionable prints to be hung on walls.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

Dutch Landscape Paintings with Livestock [*]

Dutch Landscape Paintings with Livestock [*]

“The Young Bull” (1647) (93” x 133”) by Paulus Potter (1625-1654) was considered to be one of the best Dutch landscapes; landscape painting including animals was Potter’s specialty. The bull was considered a symbol of prosperity by the Dutch, and it represented strength and confidence. This painting is an exceptionally large painting for the time. Potter added canvas to both sides and the top after it was finished in order to include other animals. Potter added a cow, the symbol of fertility, motherhood, and nurturing. Likewise, the ewe supplies milk for many Dutch cheeses. She protects her lamb, a symbol of innocence and gentleness, and reminded viewers of the lamb of God. The ram represents virility and is known for its determination and agility when climbing hills. These animals were as significant to the prosperous life of the Dutch as they are today. The landscape depicts the Dutch town of Rijswijk. A herd of cows graze peacefully on the green pasture. Potter also captures the flatness of the Dutch landscape and the cloudy sky that will bring rain to the land.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

“Methods of livestock improvements included the shortening of the period between birth and maturity for meat-producing animals. Flesh was redistributed upon the most edible parts of the body, and the weight of the animal carcass was increased. Farmers developed a number of pioneering ways to achieve these adaptations. The in-breeding and line-breeding of cattle allowed the most desirable qualities to be selected, and fixed, by mating within a single breed. Out-crossing cattle allowed for new qualities to be sought across various breeds, and fixed in one new breed by mating. The latter could also include the import and use of animals from overseas on British stock.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.