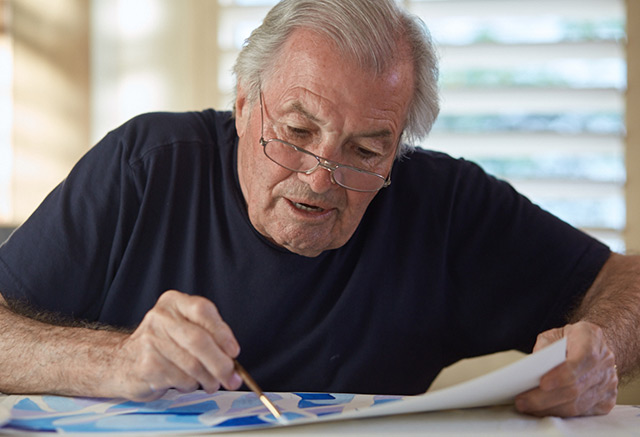

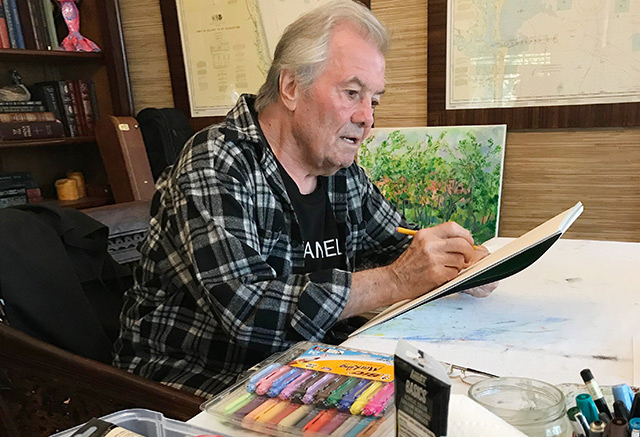

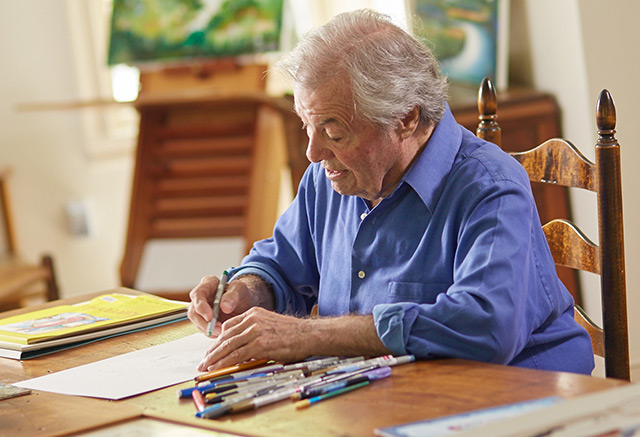

“I have been cooking for more than 60 years, and I have been painting sporadically for half a century. Both are part of who I am, how I feel, and how I react to a sensual or esthetic experience.”

“Cooking is fun, but also serious; after all, it is my métier. I am “a famous cook,” which often puts me on the spot, with people asking, “Let’s see what that guy can do!” Everyone has their own taste and their own reactions to food. If you happen to have taste that coincides with mine, I am the greatest cook; if not, you will find my food very ordinary or puzzling. On the other hand, painting is strictly fun for me and I paint only when I am in the mood. I know I am a better cook than a painter because I know cooking much better than I know painting.

I do not equate great painters and great cooks. Great painters, musicians, and writers reach a level of talent, genius, and inspiration that chefs do not attain, in my opinion. I would equate great chefs with great jewelers or great cabinetmakers. The emphasis on manual dexterity is greater in these professions than with writers, musicians, or poets. Cooking is mostly a matter of craftsmanship with talent and some inspiration added, along with a sprinkling of love for the perfect dish; one cannot cook indifferently. Certain trades, like cooking, painting, sculpting, being a surgeon, cabinet maker, mason, or jeweler, require a great deal of skill and manual dexterity.”

“Yet, there are cooks in the kitchen who have great technical skill and not much talent. I have known chefs working for 30 years behind the stove who can run a kitchen properly and are technically quite good, but their food is never really great; they have neither the palate nor the talent or imagination to take it further. Moreover, they are often unaware that they have reached the limit of their own taste. It’s difficult for a chef to admit that a food critic with limited cooking knowledge may have a larger, more complex sense of taste than he does and can analyze the chef’s dishes and be aware of his limitations when he doesn’t realize it himself. This is not said pejoratively. Conversely, some people have no technique and some talent, a situation I have found often in students and amateur cooks. They have a sense of taste and a discriminating palate, but not have much technical knowledge and ability. A dish turns out well for them occasionally, perchance, but they cannot control the quality and production of the food that is needed to run a restaurant. Without technical ability, a professional cook is like a writer without knowledge of grammar, an impossible situation.

Likewise, an art student who spends years in school learning the rules of perspective, how to mix yellow and blue to make green, and how to use a brush, a spatula, or his or her fingers, along with other technical aspects of painting, will be able to sit at an easel and create one painting after another. Does that make this person an artist? No, he or she is a craftsman at this point. However, these trained hands now have the means to express talent if talent there is. It is the same with the chef apprentice.”

“In painting, individuals who have a thorough knowledge of the techniques along with extraordinary talent, like Picasso or Matisse, are geniuses. In the kitchen, a few chefs have certainly risen higher and achieved more to become models, setting the criteria for other professionals. Chefs like Daniel Boulud and Thomas Keller are good examples, but, for me, they are still not to be compared to a Matisse or a Picasso.

In Proust’s affective memory, look, touch, taste, smell, and hearing are of the utmost importance. He developed his theory of the memory of the senses, as opposed to the memory of the brain, after eating a small cake called a madeleine that he had dipped in his tea. The taste brought him back to a youthful summer vacation where that cake had always been served with afternoon tea. The memories brought back by the taste of the madeleine were immediate, powerful, unexpected, and very deep, as compared to the memories of the brain. If you ask me to remember the cooking at the Pavillon, where I cooked in 1960, my brain memory will take me back there and I can recall it logically and discuss some of the dishes with you. I can recall the making of the striped bass roasted with shallots, white wine, mushrooms, and champagne, with the sauce finished with butter. Blindfolded I know that taste. However, if that recipe is served to me unexpectedly, the taste of it will assail me in a very acute and profound way. Memories of the taste, smell, look and texture of a dish are very important to the chef and, certainly, to the food critic. James Beard had an amazing food memory and could discuss dishes in detail going back to meals he ate in Paris in the 1950s and ‘60s. Memories of the brain are more sedate, logical, and organized.”

“So, first is the learning of techniques. Endless repetition, a kind of mechanical process, is an investment of time that is necessary for a chef. Eventually, the techniques become so much a part of the self that they will never be forgotten. Only after that fastidious process has been acquired can one think in terms of combinations of ingredients, texture, color, harmony, and complementary saveur. As long as one is impaired by the menial tasks of slicing, dicing, boning, and poaching, there is no space for talent to emerge. I am able to cook and talk at the same time to an audience on my TV show because I have transcended the level at which I have to struggle with techniques. They are a part of who I am and my hands are working almost independently of my mind. So, I have time to concentrate on combinations of color, taste, texture, presentation, and the like.

When a chef cooks at the stove, he or she doesn’t follow a recipe but the memory of a taste or a new idea. He acts intuitively, impulsively adding, correcting a nuance in a sauce or a shade in a seasoning with all the ingredients at his disposal while visualizing and aiming for that elusive “goût” or savor. Similarly, if an artist had to intellectually analyze a painting and decide that it needs a touch of blue indigo here and a trace of red vermillion there, or a soupçon of cadmium yellow in this corner, by the time the tubes of paint are open and squeezed onto the palette, the urge and the vision are gone. The colors have to be at the ready on the palette for the painter, just as a set of ingredients must be in front of a chef as he or she cooks. The process is inherent, automatic, and intuitive. The artist places that touch of color there because it feels right, it belongs there, it fits, just as a cook adds a dash of salt, pepper, or wine to a sauce to get the taste exactly right. You cannot suppress the subconscious, certainly in art, especially abstract or surrealistic, like in Dali or André Breton (1924) automatic writing, where the unconscious or subconscious is the source of inspiration.”

“When I have an idea about a dish, I can “cook it” in my head; I can follow the processes of mixing the ingredients and cooking them, and so avoid the pitfalls before actually starting the process. When I finally make the dish, the hammer may not fall exactly on the head of the nail each time, but it will fall close enough so that a few refinements of the dish usually make it taste the way I had imagined and tasted it in my head. In the professional kitchen, the chef has the opportunity to repeat a dish again and again in the course of an evening and this is an important aspect of his learning. Likewise with the musician who repeats and repeats ad nauseam the same tune to get it exactly right.

When I paint, I lack technique. I have never invested the time and the endless repetition necessary to understand the primary, secondary, and tertiary colors and other “tricks of the trade, “ like what can be done with a brush, a knife, a spatula, or a finger. I am a poor technician. It is hard for my hands to express the ideas I have in my head, because my technique is not good enough, and this is very frustrating. When one of my paintings turns out somewhat well, it’s more fortuitous or accidental than controlled.

I read somewhere that cooking is a “controlled creation,” which is an oxymoron. Yet, there is some truth in this, certainly, in the cooking process, where the talent is controlled by years of practice. Painting is a frustrating process for me, although I get great satisfaction from it. Occasionally, something magical happens, and I end up with a picture that is partially satisfying. While I sometimes feel instinctively that I’m not quite “there,” I often don’t know how to proceed forward. This is not the case with cooking, where I can analyze the process better and know whether I need more viscosity, more seasoning, or more balance in a sauce to go further in the recipe. There is a process in starting a painting that is, for me, difficult, even terrifying sometimes, but I do not experience that with cooking, because I know the processes so much better.”

“Starting in the 1970s, nouvelle cuisine emphasized creativity in the making of a recipe and the presentation of the food on the plate. It also emphasized going to the market daily, not overcooking fish, vegetables, and meat, and being mindful of the health of your customers. Additionally, it advised chefs to simplify recipes and shorten sauces. This was all good advice. Unfortunately, many chefs only remember the part that dealt with the creativity and presentation edicts.

Creativity is often a Pandora’s box, giving license to chefs to combine the weirdest of ingredients, just for the sake of shock. Arranged on oversized plates, these ingredients were “over-touched,” to quote Julia Child, and symmetrically arranged with tiny baby vegetables and meat sliced ahead, which tends to bleed it, cool it, and dry it out. On these over-decorated plates the food becomes stagnant, losing its spontaneity and natural quality—it is “mortician food.” However, when the taste is secure, there is nothing wrong with a nice presentation, but it should never be at the expense of taste.

Edmond Saillant, under his nom de plume, Curnonsky, wrote about regional and women’s cooking in the early 20th century. He famously said that food should have the taste of what it is, and there is certainly truth in his statement. There is nothing better than a tomato right out of the garden embellished with only the best possible olive oil and a dash of fleur de sel; it’s all about the tomato. This is focusing on linear food, but there are also the symphonic dishes.”