“Food brings people together on many different levels. It’s nourishment of the soul and body; it’s truly love.”

Giada De Laurentiis

Art UK: “Food and Feasting in European Art History” [*]

Art UK: “Food and Feasting in European Art History” [*]

“Food is more than a form of survival and nourishment. It also symbolises traditions, entrenched attitudes and even geopolitics. For example, Europe’s insatiable appetite for sugar, coffee and tea from the sixteenth century onwards was one of the driving forces behind the expansion of colonies and empire. Famine and the scarcity of grain in France in the 1770s was one factor among many that led to the French Revolution, further sparked by (almost certainly false) allegations that Marie Antoinette had proclaimed: ‘Let them eat cake!‘

In Greek mythology, Dionysus was the god of the grape harvest, wine, pleasure and fertility who was later adopted by the Romans as the god Bacchus. An embodiment of hedonism, inebriation and bodily abandon, Dionysus and Bacchus were typically portrayed at a drunken banquet, dining and boozing it up among the satyrs, maenads and bacchantes. Apart from wine, Bacchus was also the god of agriculture and is usually depicted next to vines and grapes.”*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

Ink World: “The Most Iconic Food Art in History” [*]

Ink World: “The Most Iconic Food Art in History” [*]

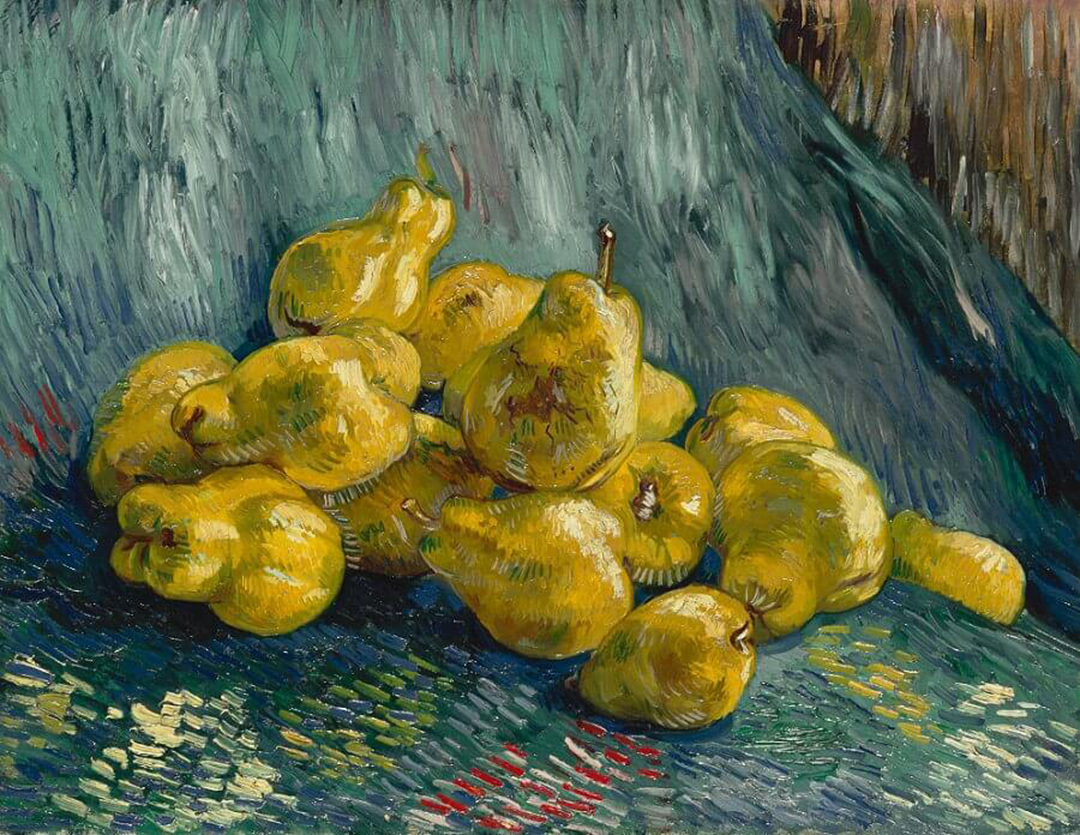

“Art featuring foods like juicy fruits, vegetables, meats and carbs, has been with us since the beginning. Often these images show one thing but reveal another, be it wealth or societal critiques. Other times it just makes us hungry. Here’s a quick walk through the history of food art. Some of the first recorded food images come from Egypt. Hieroglyphs show crops and bread sketched on Egyptian pyramids, dating as far back as 3,300 BC.

The Greeks and Romans were all for it, too. Roman paintings often featured glass bowls filled with fruit to indicate the wealth and generosity of Rome. Then there were the Roman gods who were all about food. Bacchus, the god of wine, was linked with grapes, symbolizing a happy afterlife. Wheat was covered by Ceres, the grain goddess, who represented vice and virtue. Here’s Eros picking grapes.

Now we come to food art laden with sex symbolism. Note the woman eying the viewer while chopping up a cabbage, which represents female sexuality. In the background a man grips a large carrot. Yes indeed. And for those paying close attention, in the left hand corner a cucumber is stacked between two tomatoes. Subtly was not on the cards in 1569. ”*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

Artists Network: “Binge! The Food Feasts of Art History” [*]

Artists Network: “Binge! The Food Feasts of Art History” [*]

“Let the feasting begin. As many of us prepare for, or are already in the midst of, this season of holidays, parties and fun, we decided to feast with our eyes first with a totally binge worthy showcase of food feasts of art history! It’s an artist’s cornucopia of gorgeous, strange and sometimes a little bit gross artworks featuring edibles. Annibale Carracci’s The Bean Eater is a depiction of a rough and tumble character sitting down to a hearty meal. With eyes looking directly outward, there’s an implied expectation that you, the viewer, are sharing his space and the dining hour, perhaps at a table across the way.

A dark and coarse supper from the Post-Impressionist Vincent Van Gogh, The Potato Eaters is unlike the painter’s colorful landscape masterworks. The artist focused on the poverty and realness of peasants at table. In a letter, Van Gogh describes:

“You see, I really have wanted to make it so that people get the idea that these folk, who are eating their potatoes by the light of their little lamp, have tilled the earth themselves with these hands they are putting in the dish, and so it speaks of manual labor and — that they have thus honestly earned their food. I wanted it to give the idea of a wholly different way of life from ours — civilized people. So I certainly don’t want everyone just to admire it or approve of it without knowing why.”

Egyptian hieroglyphs depict agriculture at its most ancient. Food was a mainstay of tomb decorations because who wants to get hangry in the afterlife? One tomb features a couple at work planting and harvesting. Other paintings show figures in similar moments of farming. Still others depict servants processing with platters of fish, fruit and game. It also turns out grains, despite art to the contrary, made up the bulk of the Egyptian’s diet from 3500 BC to 600 AD, with little meat and surprisingly little fish as well considering, well, the Nile.”*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

“In the world of art, banquets and markets have been widely investigated pictorial objects, and among the many stand out: the Wedding Banquet of Cupid and Psyche by Raphael and the Vucciria Market by Renato Guttuso. In spite of these examples, however, the most famous association between art and food took the form of still lifes, pictorial representations of inanimate objects, whose popularity spread especially between the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth century, eras in which the taste for less demanding subjects compared to the traditional ones, such as: history painting, portraits and landscape painting, was imposed. The greatest development of the pictorial representation of inanimate objects took place in Northern Europe, since the Protestant religion had forbidden to portray religious subjects. In Italy, however, the first to make famous the genre of still life was Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio.

Caravaggio’s Canestra di Frutta (Basket of Fruit) is considered the incunabulum of the still life genre in Italian art, because before this masterpiece, inanimate objects were mostly depicted only as simple ornaments and decorations. Consequently, Merisi’s work, in which fruit is the protagonist, gives a new dignity to this genre, raising it to the level of figurative painting. What has been said is surely due also to the pictorial talent of the artist, who was able to carry out a real realistic investigation of the depicted subject, so much so as to report even its imperfections. As for the description of the painting, at the center of the work is placed a basket of woven wicker, where, inside, is placed fruit of various kinds. This subject, within a bare neutral background, rests on a wooden plane visible only at its extremities, which runs parallel to the viewer’s gaze. In contrast to the simplicity of the setting, the fruit has been painted with masterly precision, so that its smallest details and defects, such as holes and dust, are visible. Finally, by representing things simply as they appear to us and without any filter, Caravaggio revolutionized the way still life is depicted.”*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

Hyperallergic: “A Food-Obsessed Frolic Through Western Art History” [*]

Hyperallergic: “A Food-Obsessed Frolic Through Western Art History” [*]

“The artist François Boucher knew how to use food as a ruse. The Rococo master’s 1746 painting “Pensent-ils au raisin? (Are They Thinking about the Grapes?)” presents a tempting scene of consumption. Lounging amid goats and sheep under feathery trees, a young lady in a blush-colored gown extends a single grape towards her shepherd-lover’s mouth. The grape is the exact hue of her own flesh, and the shepherd’s fingers gently cradle the bunch that she dangles over her lap. The work’s now-famous title — later immortalized in a widely circulated print by Jacques Philippe Le Bas — reflects Boucher’s winking, playful sensuality. After all, who would be worried about grapes, or any other food, at a seductive moment like this?

As it turns out, Leonard Barkan would. His book The Hungry Eye: Eating, Drinking and European Culture from Rome to the Renaissance (Princeton University Press) is a food-obsessed frolic through the artwork, writing, and philosophy of hundreds of years of Western history. A Renaissance scholar, art historian, and food and wine writer, Barkan organized his book according to his self-proclaimed ‘hungry eye,’ which roves from Pompeiian mosaics to Bible passages to Shakespearean plays in search of food and drink. This approach, which Barkan calls “reading for food,” interrogates occurrences of hunger, thirst, flavor, and pleasure in ancient to early modern culture as catalysts for new interpretations of life and meaning in the Western world.”*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.