“The human body is the best picture of the human soul.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein

The Tate: “Human Figure Coursework Guide” [*]

The Tate: “Human Figure Coursework Guide” [*]

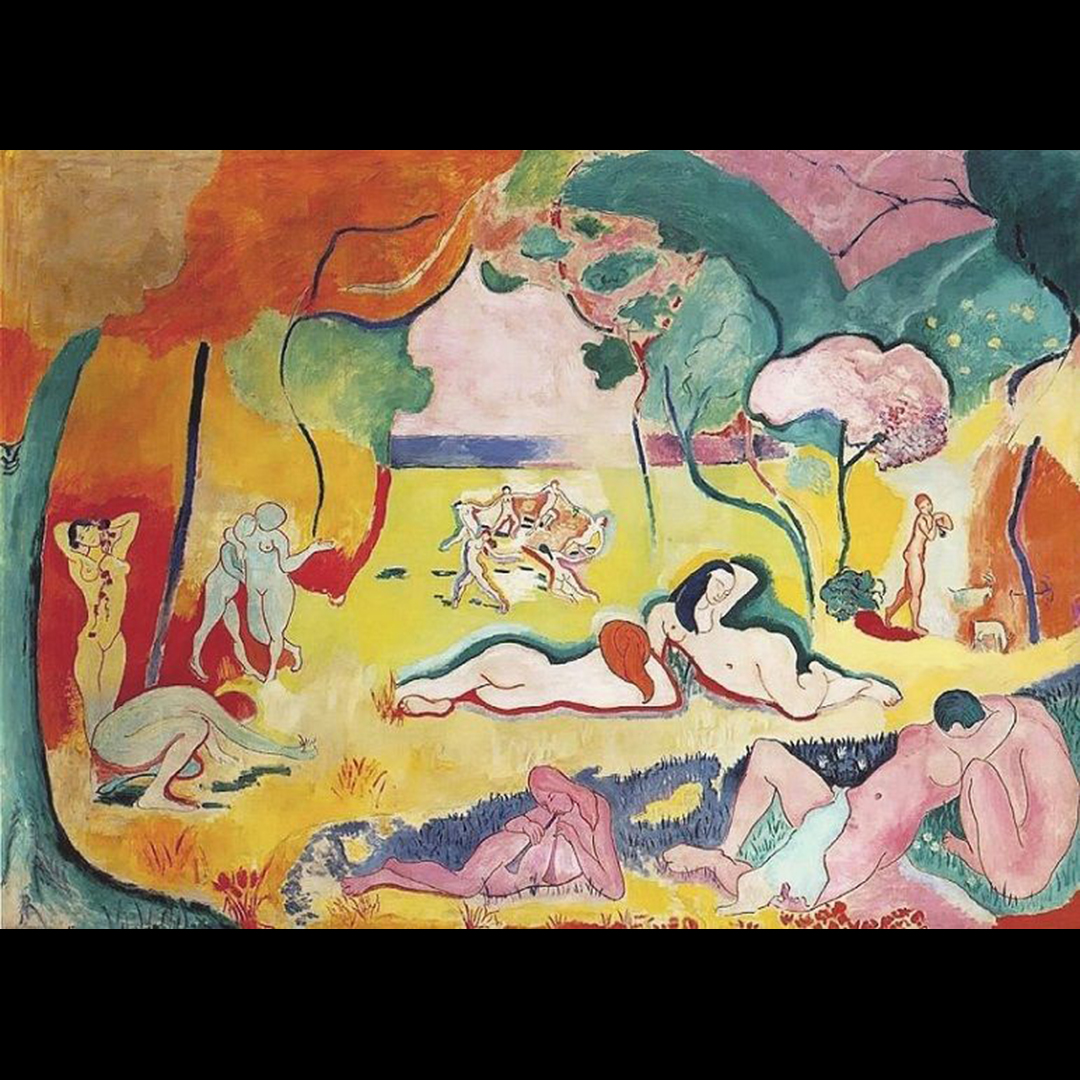

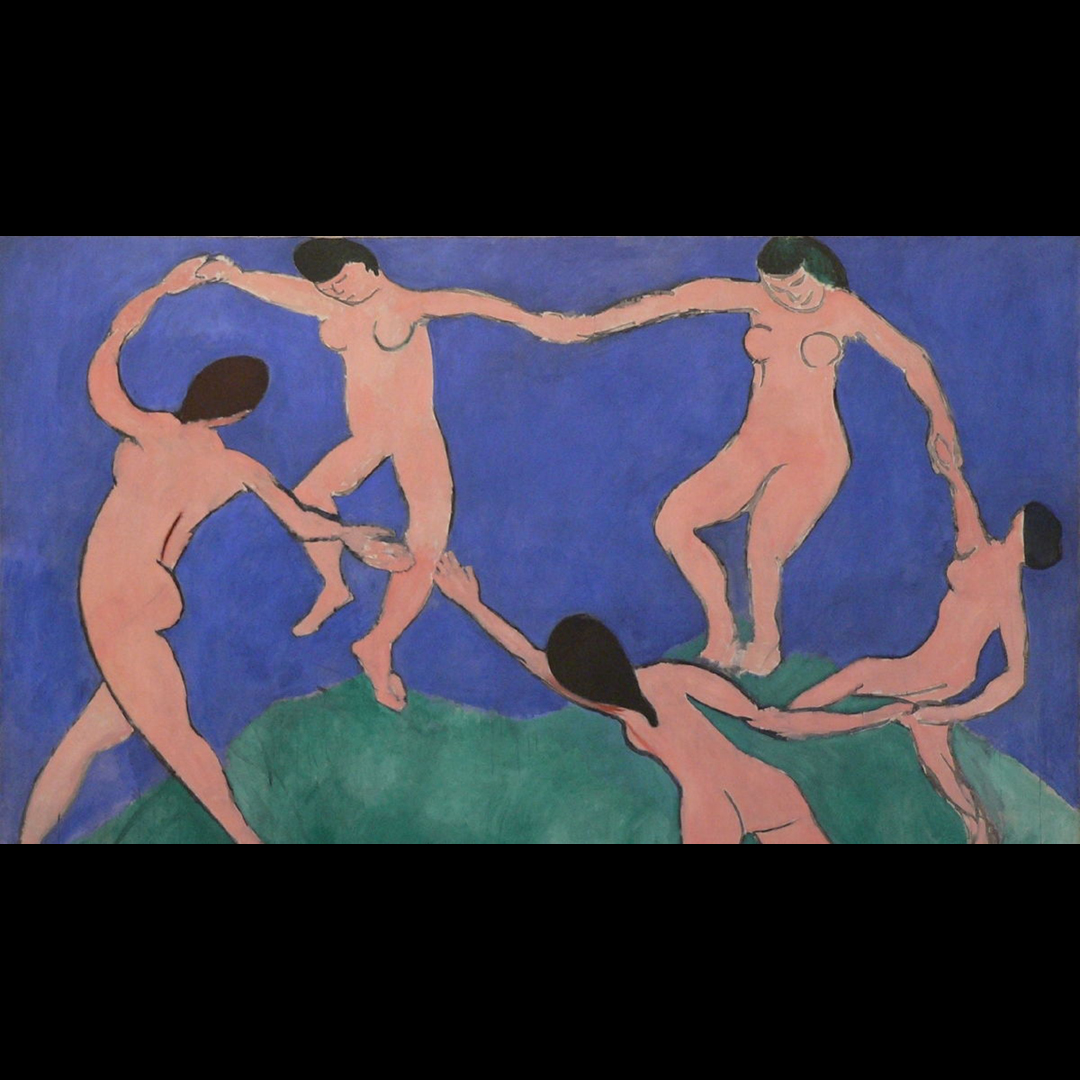

“For thousands of years the human figure has appeared in art. Early cave paintings show figures of hunters simply depicted using a few strokes. In ancient Greece human figures were the main subject on decorated vases. Through the ages the human figure has appeared in portraits, has been used to tell stories or express beliefs, or used to explore what it is to be human. At art school drawing from the human figure is often one of the first skills taught. Life drawing helps young artists to look closely and understand proportions, as well as experiment with techniques.

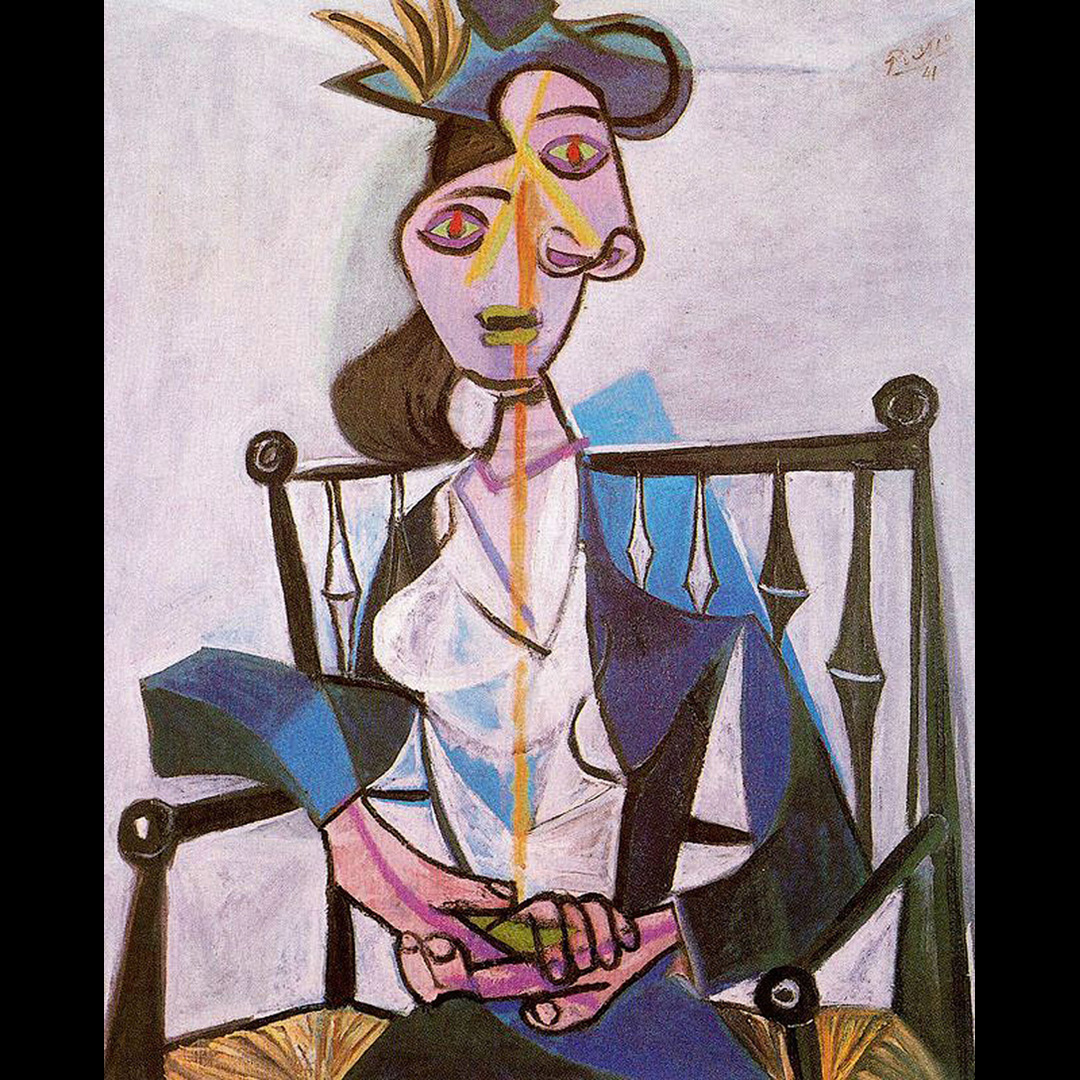

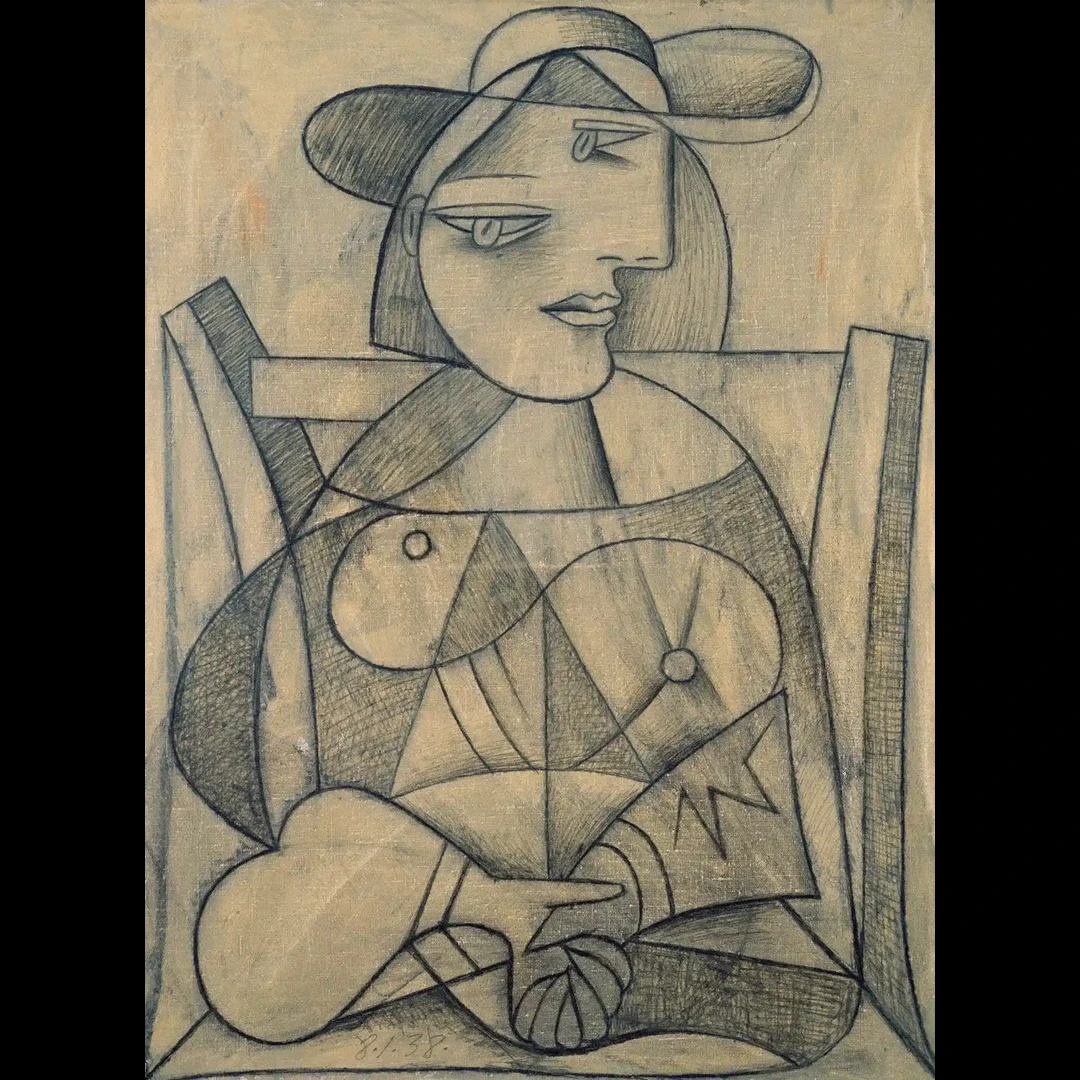

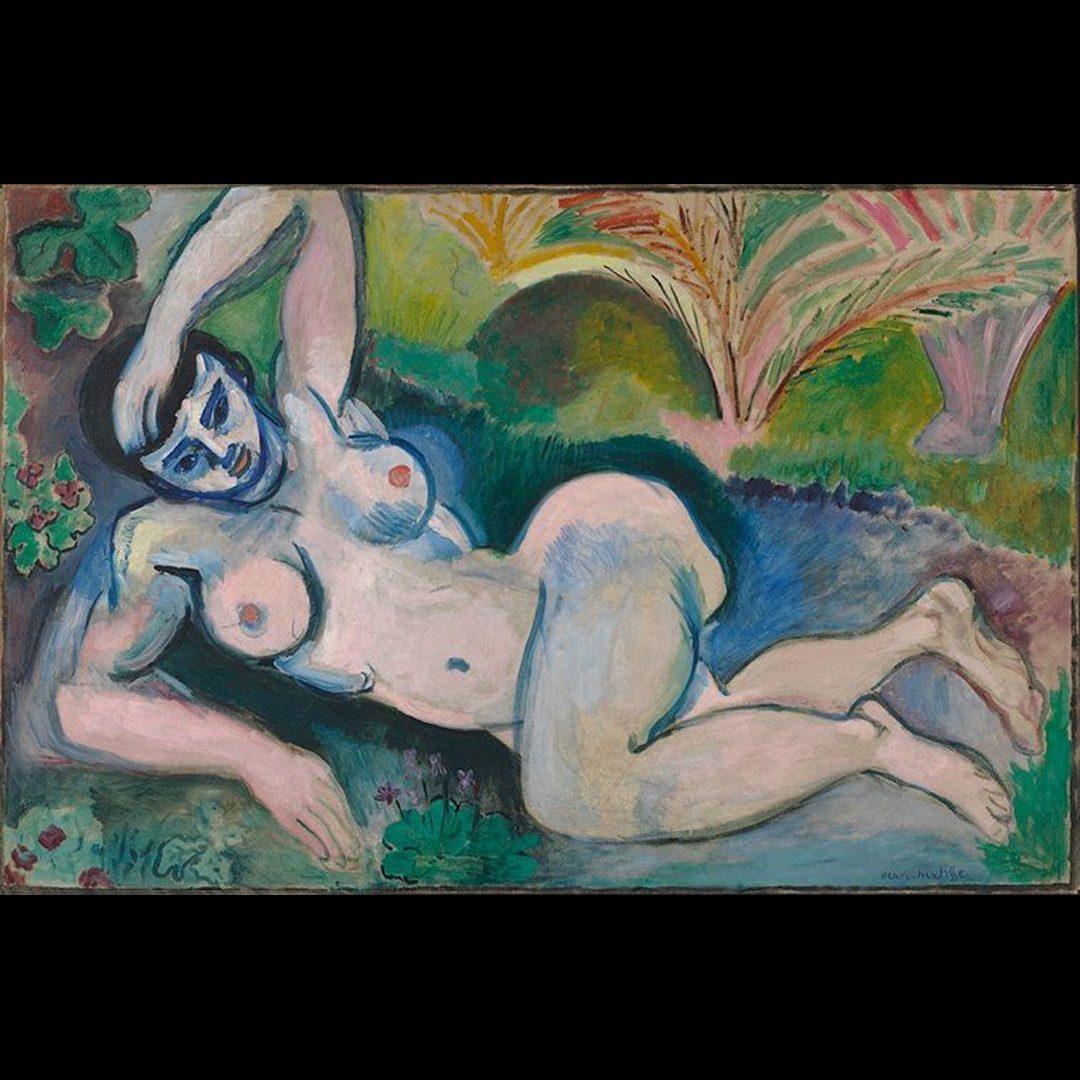

Explore some of the ways artists have drawn and painted the human figure from life: For most artists who draw, paint – or sculpt – ‘from life’ their fascination with the human figure is much more than simply creating an accurate representation of their model. The painter Lucian Freud spent 60 years drawing and painting the human figure, mainly using friends and family as his models. Although his drawings and paintings of people look like straightforward depictions, there is a psychological intensity to many of the portraits. The figures often seem awkward and their poses suggest vulnerability. As well as the phsyical nature of the human figure, Freud seems to also be exploring the emotional fragility that we as humans sometimes experience.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

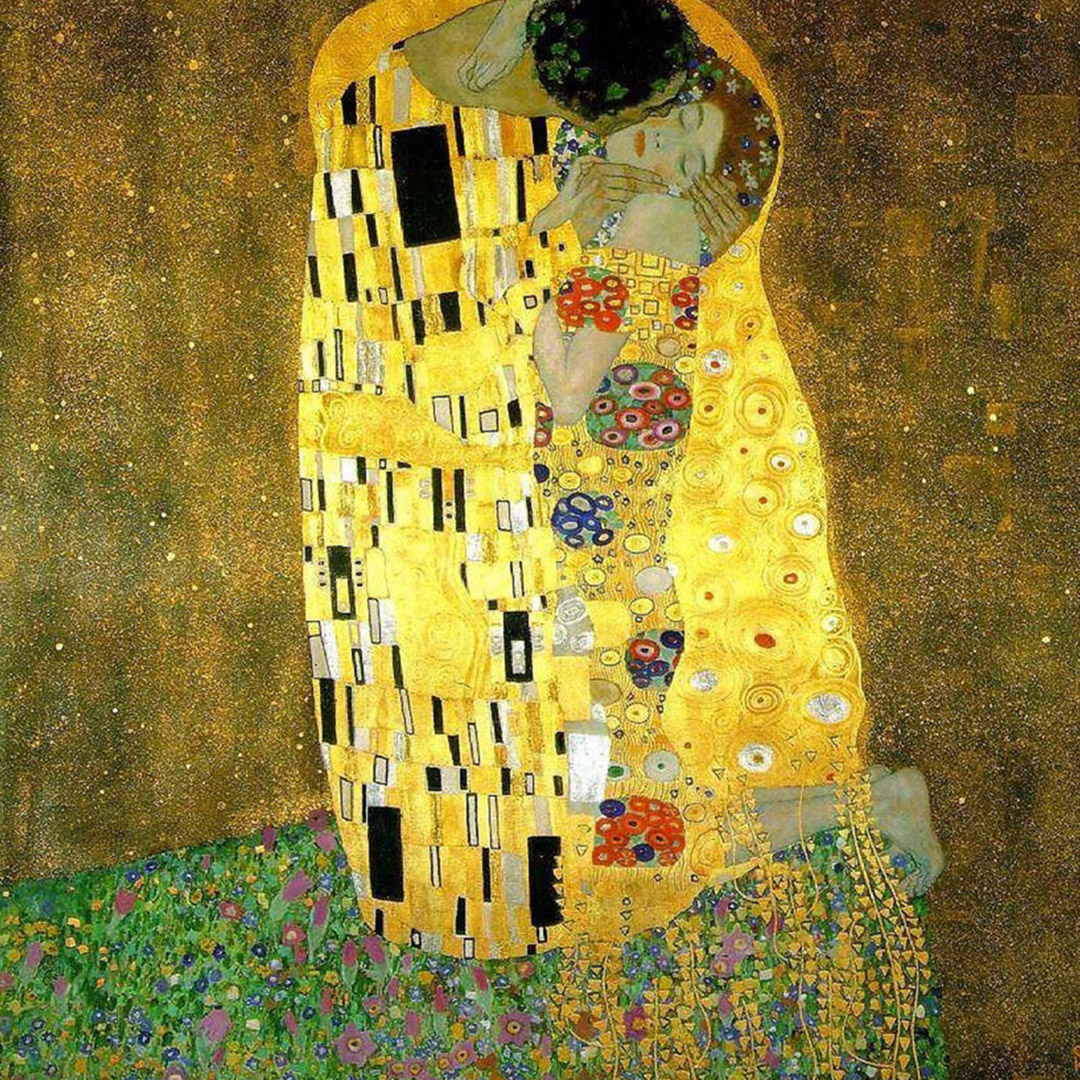

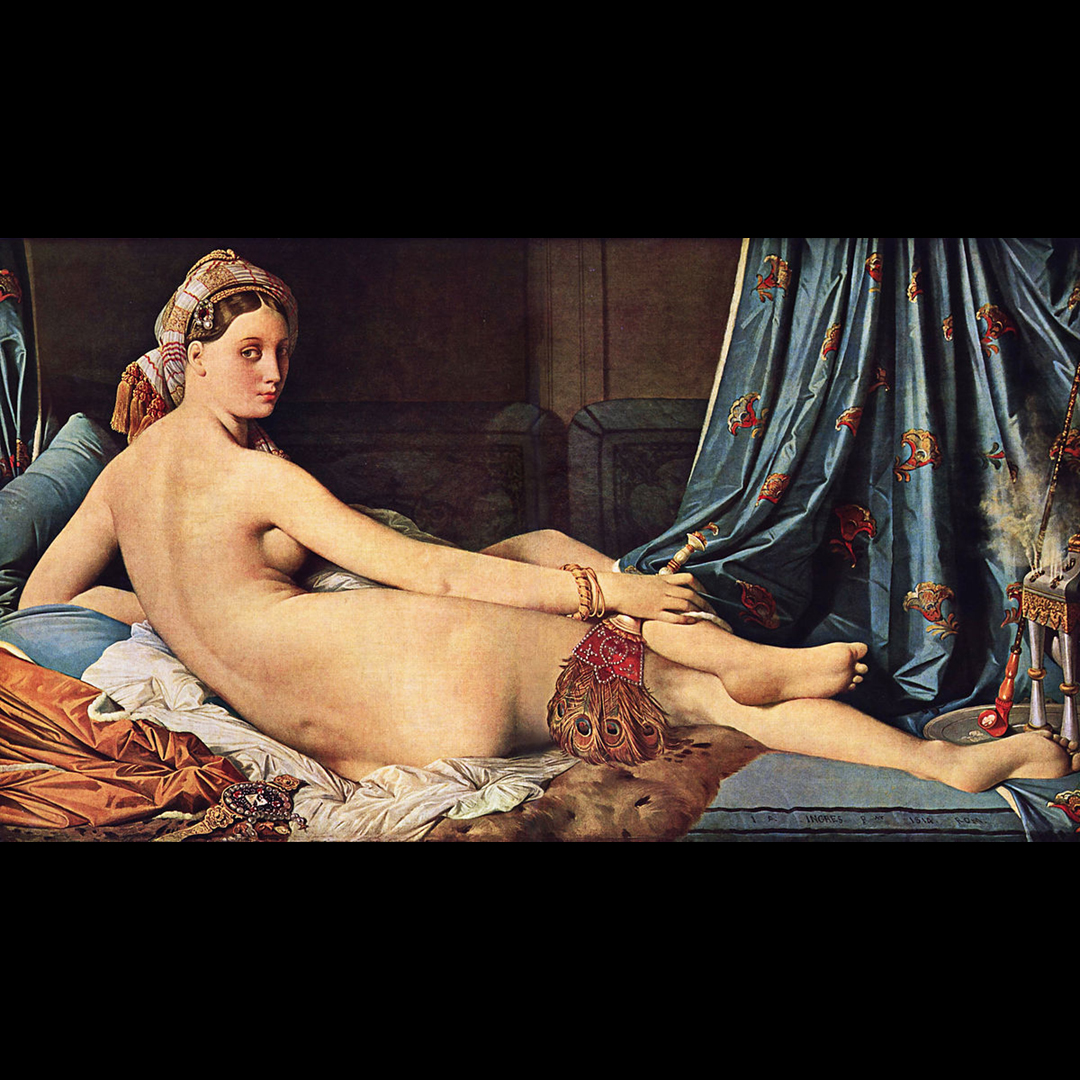

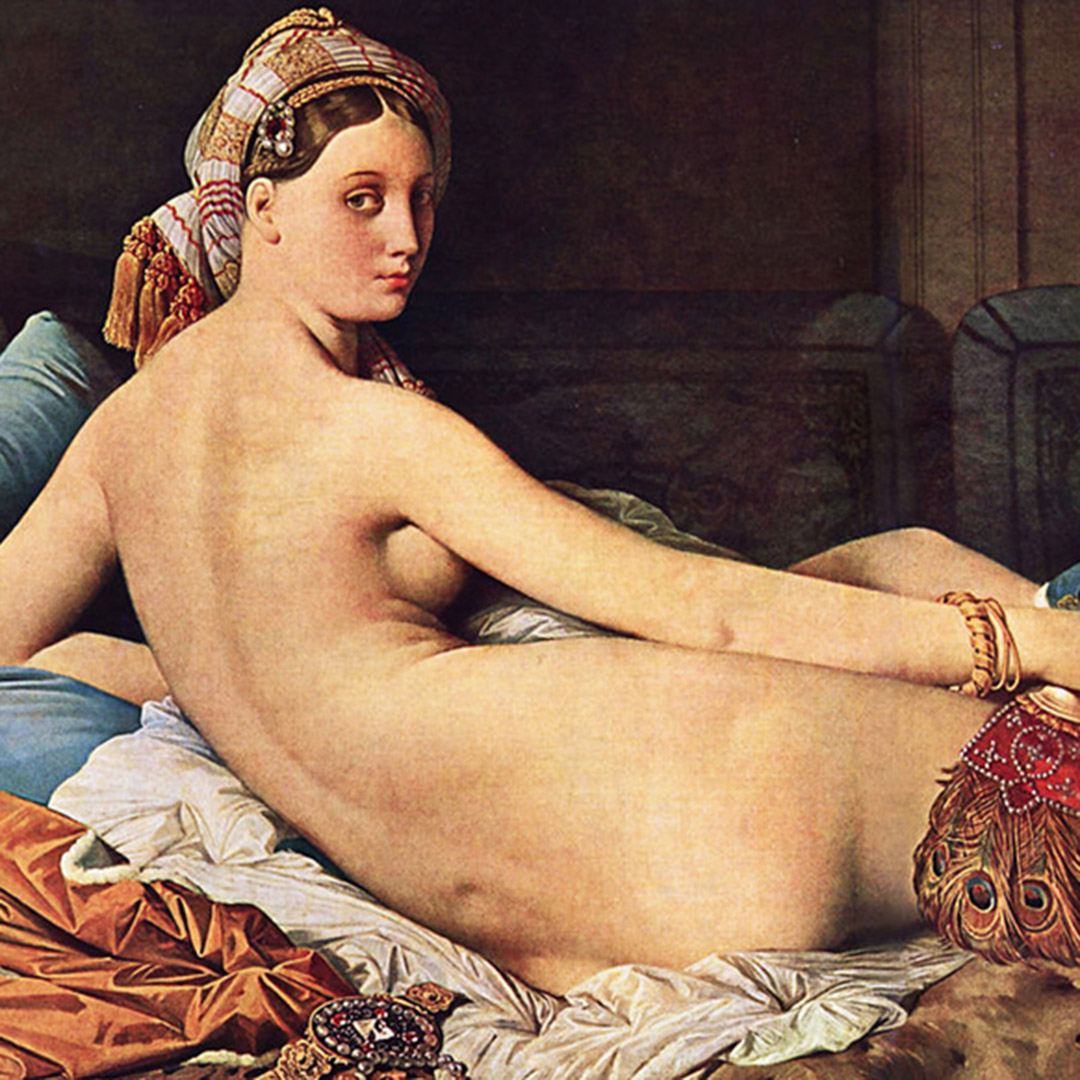

“The human body is central to how we understand facets of identity such as gender, sexuality, race, and ethnicity. People alter their bodies, hair, and clothing to align with or rebel against social conventions and to express messages to others around them. Many artists explore gender through representations of the body and by using their own bodies in their creative process.

The 1960s and 1970s were a time of social upheavals in the United States and Europe, significant among them the fight for equality for women with regards to sexuality, reproductive rights, the family, and the workplace. Artists and art historians began to investigate how images in Western art and the media—more often than not produced by men—perpetuated idealizations of the female form. Feminist artists reclaimed the female body and depicted it through a variety of lenses.

Around this time, the body took on another important role as a medium with which artists created their work. In performance art, a term coined in the early 1960s as the genre was starting to take hold, the actions an artist performs are central to the work of art. For many artists, using their bodies in performances became a way to both claim control over their own bodies and to question issues of gender.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

The Met: “Anatomy in the Renaissance” [*]

The Met: “Anatomy in the Renaissance” [*]

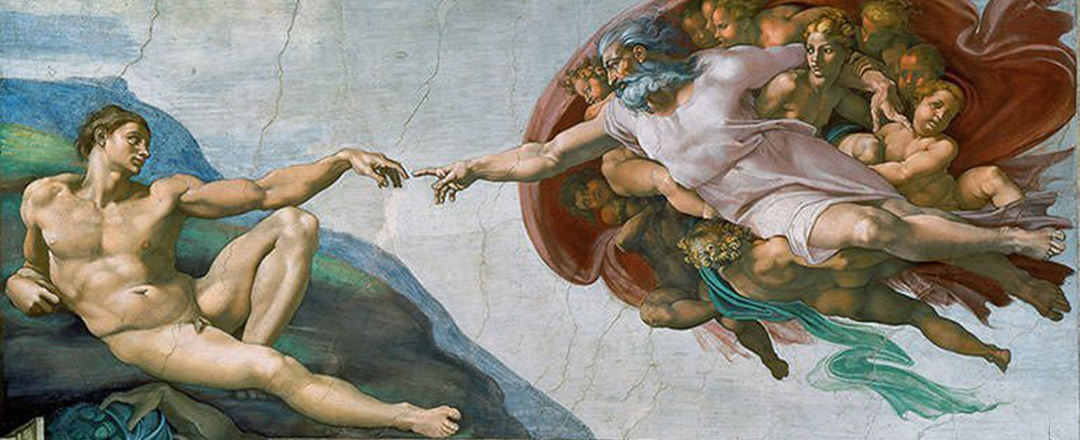

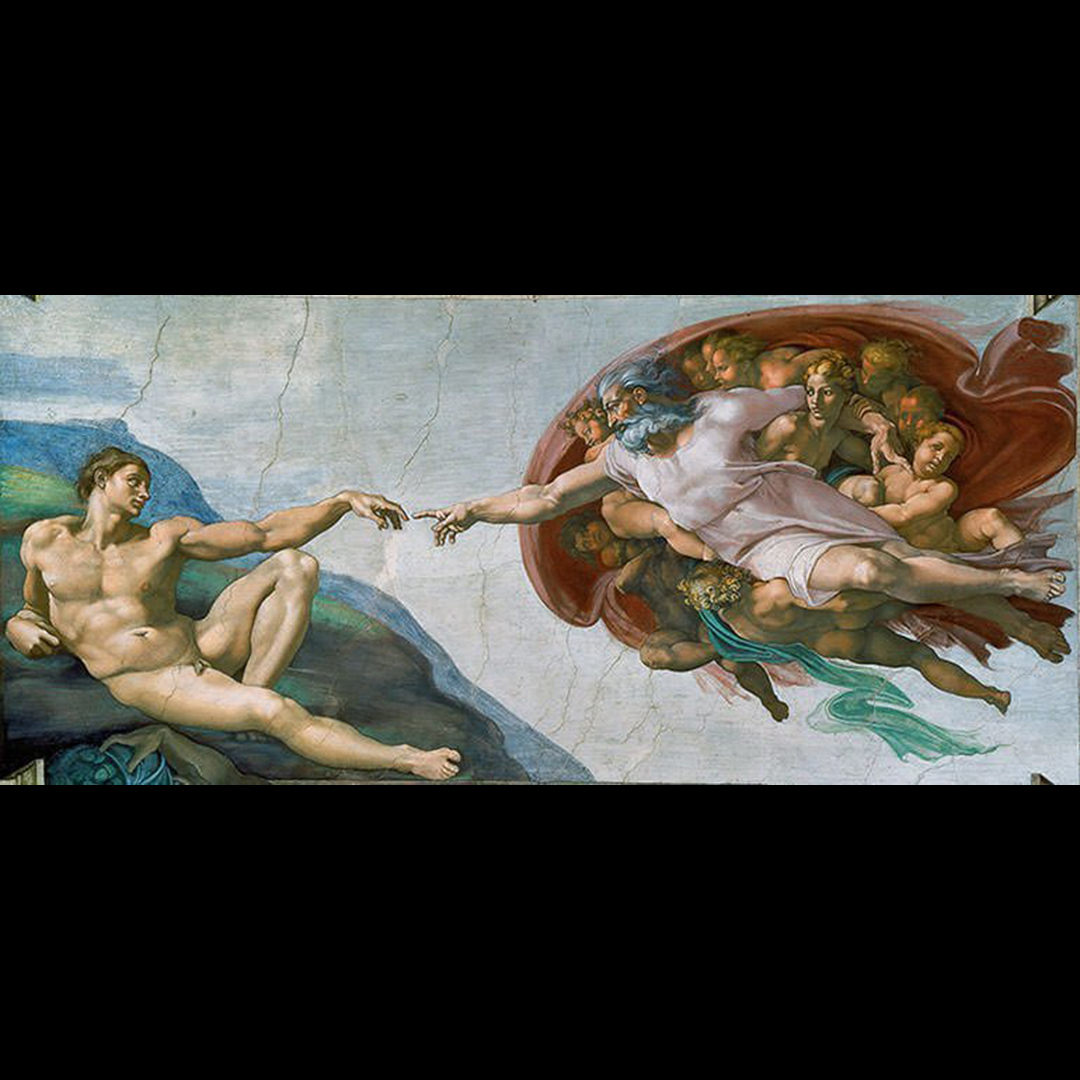

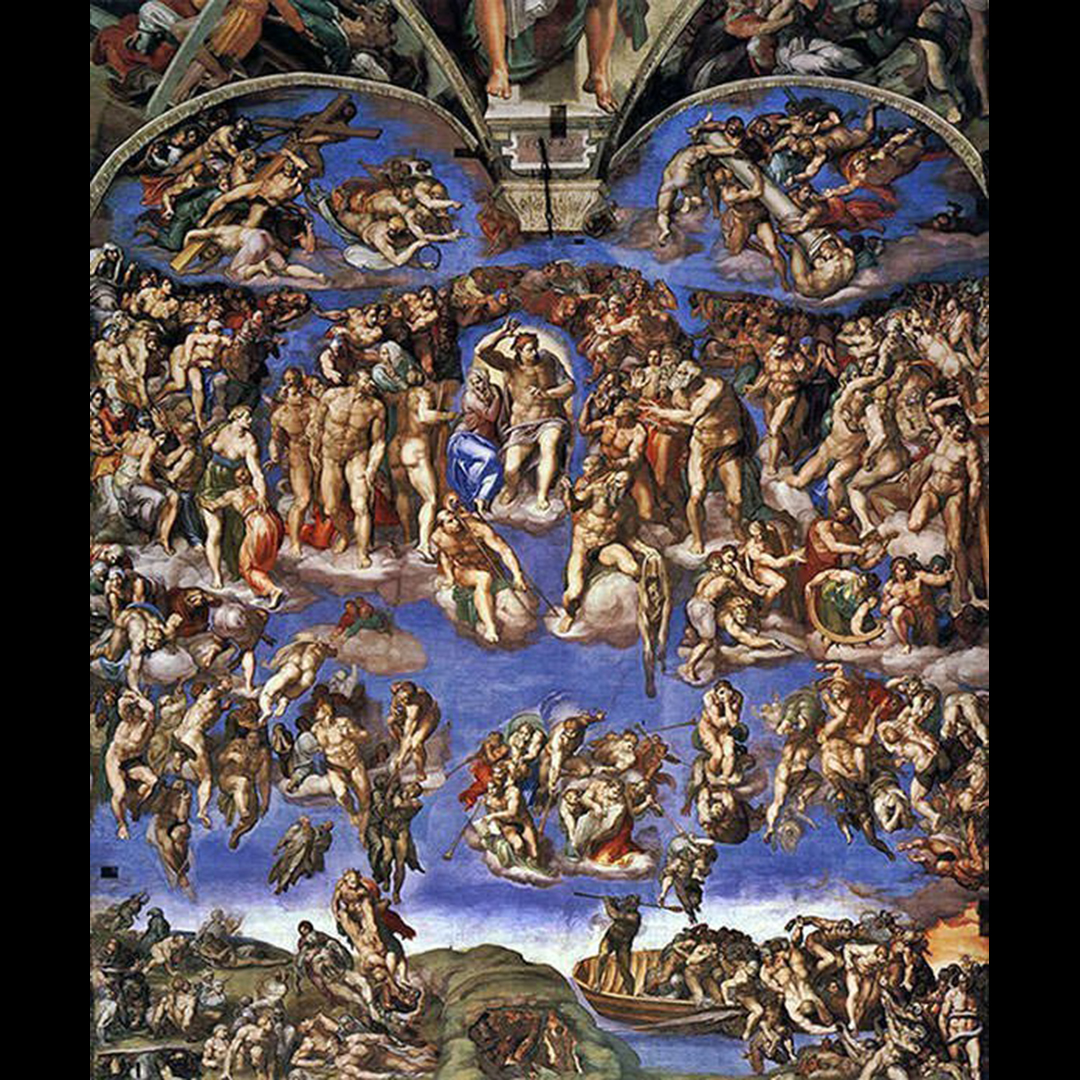

“Italian Renaissance artists became anatomists by necessity, as they attempted to refine a more lifelike, sculptural portrayal of the human figure. Indeed, until about 1500–1510, their investigations surpassed much of the knowledge of anatomy that was taught at the universities. Opportunities for direct anatomical dissection were very restricted during the Renaissance. Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists states that the great Florentine sculptor, painter, and printmaker Antonio Pollaiuolo (ca. 1432–1498) was the “first master to skin many human bodies in order to investigate the muscles and understand the nude in a more modern way.” Giving credence to Vasari’s claim, Pollaiuolo’s highly influential engraving of the Battle of Naked Men displays the figures of the nude warriors with nearly flayed musculature, seen in fierce action poses and from various angles.

The later innovators in the field, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Michelangelo (1475–1564), who are known to have undertaken detailed anatomical dissections at various points in their long careers, set a new standard in their portrayals of the human figure . The patrons commissioning art in this period also came to expect such anatomical mastery. In the words of the Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli (1493–1560), who was trying to impress a duke to hire him, and who also appears to have run an academy for the teaching of young artists, “I will show you that I know how to dissect the brain, and also living men, as I have dissected dead ones to learn my art” . Circumstantial evidence suggests that a number of other artists also attempted direct dissections. Some later great masters produced écorchés, studies of the peeled away or ripped apart forms of muscles, to explore their potential for purely artistic expression. The majority of artists, however, limited their investigations to the surface of the body—the appearance of its musculature, tendons, and bones as observed through the skin—and recorded such findings in exquisitely detailed studies after the live nude model.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

Here we offer a quick tour of how artists have rendered the human form throughout history: