“Abstract art is not the creation of another reality but the true vision of reality.”

Piet Mondrian

Rise Art: “Abstract Art: Examples Throughout History” [*]

Rise Art: “Abstract Art: Examples Throughout History” [*]

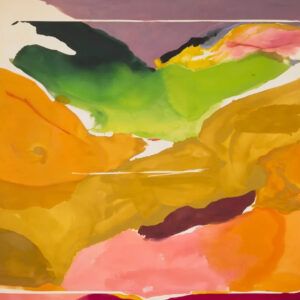

“Abstract art, in practice, is the creation of artwork that does not explicitly represent reality but uses a multitude of shapes, colours, forms and marks to achieve an effect. The style evolved throughout the 1900s, giving way to sister movements such as Expressionism, Abstract Expressionism, Cubism, Orphism, Suprematism, Constructivism, Automatism, Colour-Field Painting, and more still. With its many modes and materials, the abstract system has yielded some of the world’s most-loved and memorable pieces of all time. Here are some examples.”

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.

Ideal Art: “Defining Moments in the History of Abstract Art” [*]

Ideal Art: “Defining Moments in the History of Abstract Art” [*]

“Words can be so controversial. We just want to discuss the history of abstract art. But that sentence is rife with conceptual peril. (Whose history? What is art? What does it mean to be abstract?) To be precise, maybe we should title this article something like, “Defining Moments in the Chain of Events Comprising the Generally Accepted Timeline of Western Civilization Relating to Objects and Phenomena Created by Self-described Artists Not Intending to be Representational of Objective Visual Reality.” But that’s not exactly a clickable headline. (Or is it?) For the sake of sanity, for this article let’s put semantics aside and just start at the beginning.

The Pre-History of Abstract Art: Among the earliest marks of prehistoric cave dwellers were lines, scratches and handprints. Our best interpretation is that they were symbolic. So does that make them the first examples of abstract art ? Perhaps. But even the representational images left behind by our ancient ancestors aren’t exactly photo-realistic. What’s missing in our analyses is an understanding of our earliest artists’ intent. When we talk about abstract art, we mean art that was specifically intended to be abstract. Since we cannot know what prehistoric artists intended to communicate through their images, we cannot judge whether it was abstract, or even whether it’s art. It could have had utilitarian purposes for all we know. So we’ll skip ahead, way ahead, to a time better documented, when artists’ intentions were clearer.

Calling All Romantics: Prior to the early 1800s, it’s safe to say the vast majority of artists the vast majority of the time didn’t have the luxury of deciding what they’d make. Most pre-Romantic Era artists relied on the support of religious institutions or some other authoritarian power in order to survive. Kings and holy men therefore determined the subject matter of most of those artists’ works. As that system of patronage declined, other modes of survival presented themselves to artists. A gallery system emerged; independent art dealers began representing the work of artists; wealthy individuals and private institutions began supporting artists and collecting their works. For the first time, artists were given the chance to answer for themselves the question, “What do I want to make?” Immediately came the next inevitable question: “Why do I want to make it?” The answer to that question is a leading cause of the eventual rise of abstract art, and is perhaps the most enduring concept to emerge from the Romantic Era; one expressed by many thinkers of the time, and summed up by the French as, “L’art pour l’art.” Art for art’s sake. Or as the writer Edgar Allen Poe put it in 1850:“…would we but permit ourselves to look into our own souls we should immediately there discover that under the sun there neither exists nor can exist any work more thoroughly dignified, more supremely noble, than this very poem…written solely for the poem’s sake.””

*Quotation above is taken directly from the website cited and is the property of that source. It is meant to inform the reader and to give credit where it is due.